The journey from high school athlete to college competitor has changed dramatically over the past few decades. What once relied on performance, personal growth, exposure, and coach connections has become a complex process shaped by technology, metrics, and money. Faculty who participated in D1 sports from different eras illustrate how the path to college athletics has shifted and why today’s athletes face a very different landscape than those who came before.

According to Coach Schultz, who played baseball at Loyola Marymount University (1998-2000), the traditional pathway was once more straightforward: getting on a team used to be about “high school performance, summer ball, and exposure through traditional scouting channels.” During his time, being seen by coaches mainly depended on live games, consistent performances, and patience. Today, Schultz observes, athletes “navigate a year-round evaluation process that starts earlier, moves faster, and involves far more variables.” Showcases, travel teams, social media, analytics, and early verbal commitments have raised both visibility and significant pressure on young athletes.

Modern recruiting reflects these changes. Pipeline Sports Performance explains that today’s athletes are evaluated with detailed metrics like exit velocity, spin rate on pitches, and advanced video analysis. This is on top of live performance, making talent measurement more accessible. Coaches are now attending large events where they can scout lots of prospects all at once, rather than focusing on individual high school games.

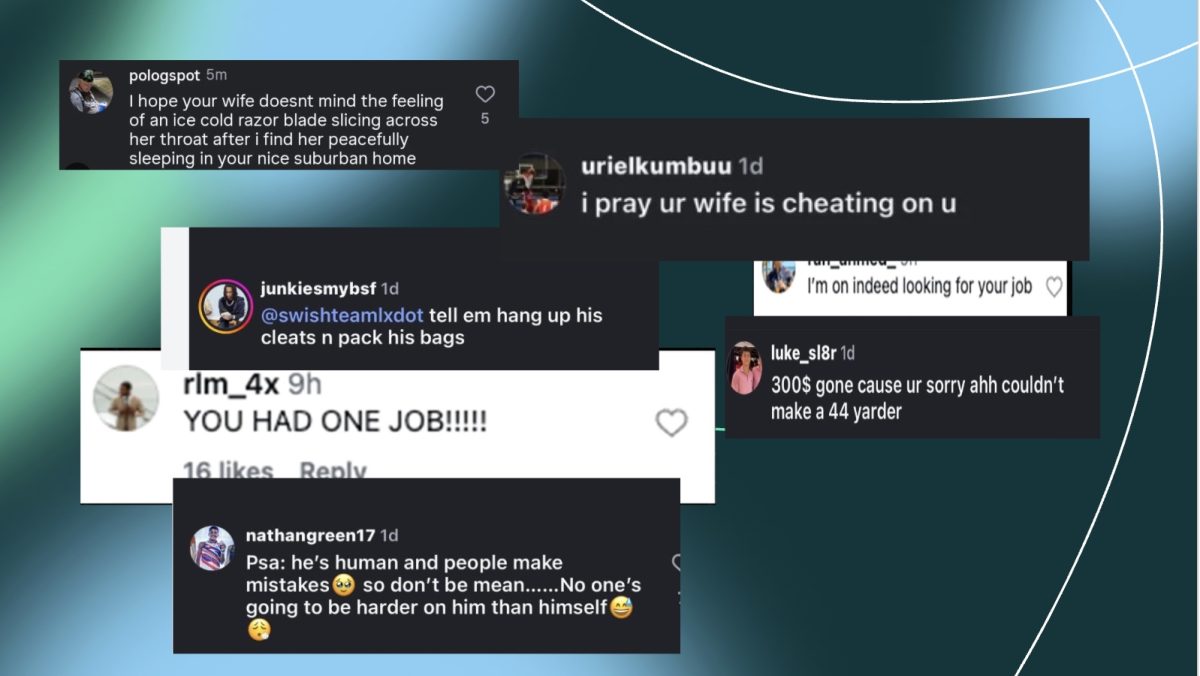

This shift aligns with stories in The Changing Landscape of College Athletics, which notes the evolving business of college sports. Increasing commercialization, flexibility with scholarship money, and many financial incentives, such as NIL (name, image, likeness) opportunities, have made recruiting a strategic competition not just for talent but also for their branding. Dr. Harry, a researcher from the University of Florida, even said, “With the shifts in NIL policies, athletes are starting to develop roles and identities related to that of the influencer.”

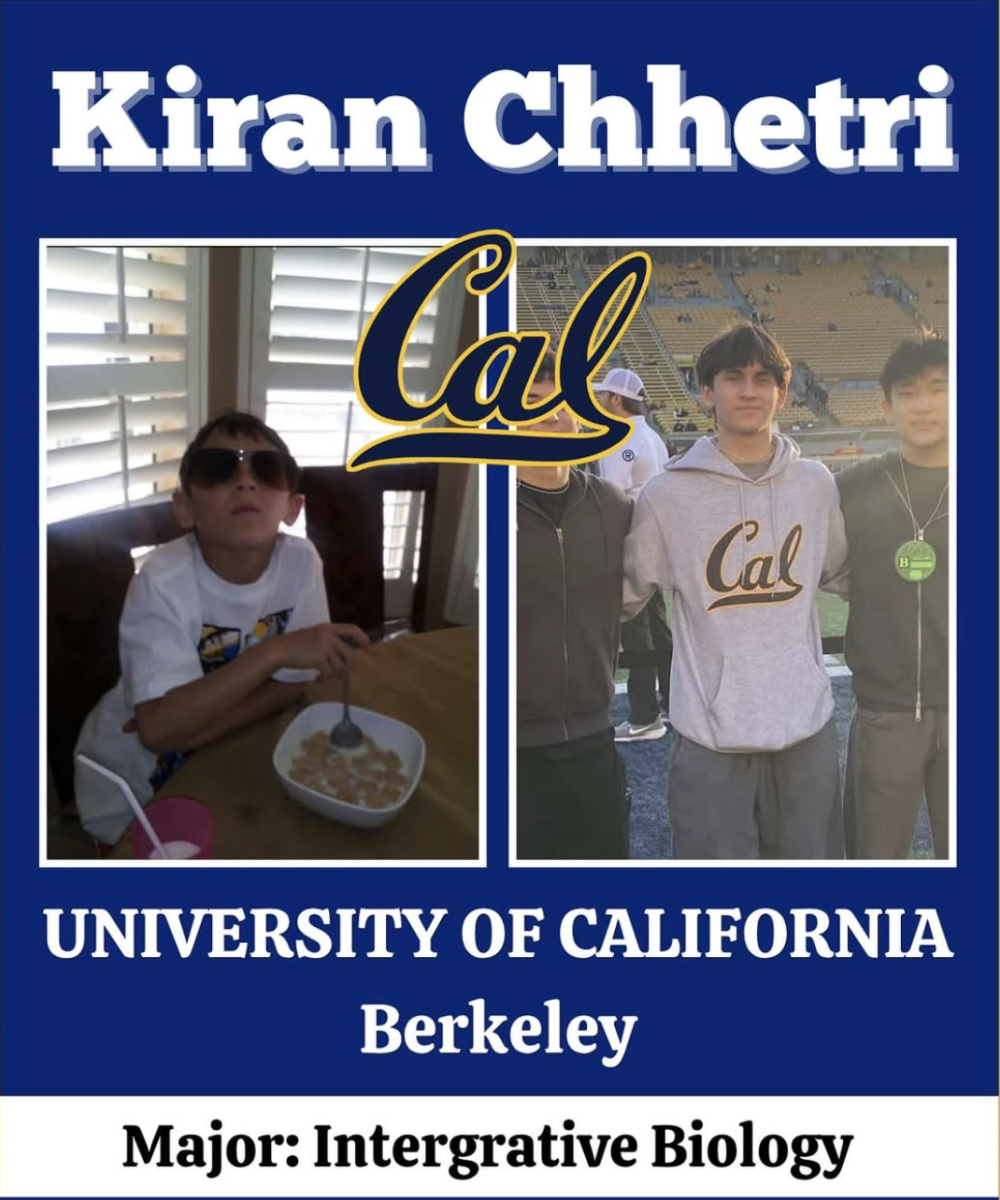

Coach Castro, a younger-generation coach, played college basketball in the Philippines (1998-2000). He recalls a time when high school competition was the only way to be seen by coaches, which was in a time when social media didn’t exist. High school coaches relied on their networking to help their athletes get noticed. Today’s recruiting is often even earlier, since exposure happens through AAU (Amateur Athletic Union) events and digital platforms. Castro noted that although it was harder to be seen back then, once a player made college, coaches were more patient with their growth, maybe keeping them for 4-5 years. Now, early specialization and the transfer portal have raised competition and reduced roster stability. So, athletes would transfer to different programs earlier in their collegiate years.

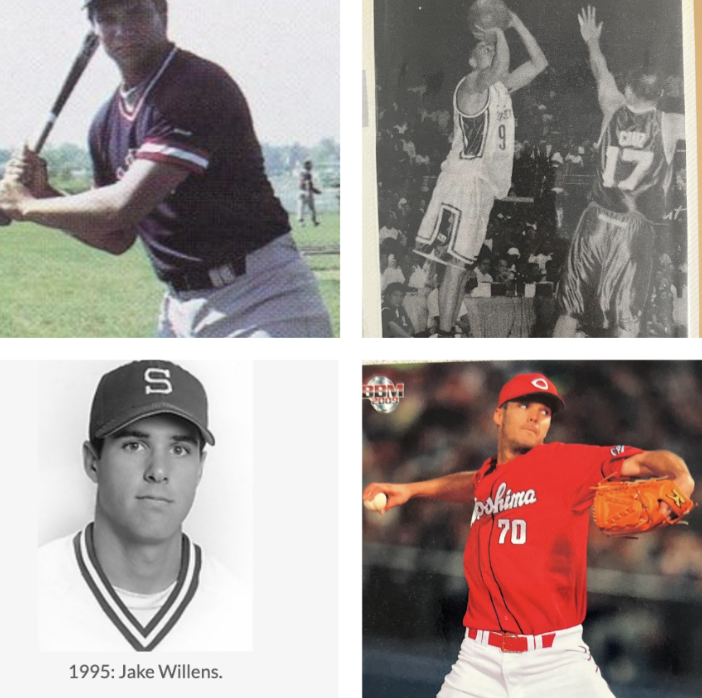

Meanwhile, Mr. Willens, a teacher who played baseball at Stanford (1995), emphasizes how the internet has changed recognition: “It is easier to promote yourself now with the internet and social media … in some ways also harder because more people can put themselves out there and try for a certain number of spots.” His perspectives show the contrast between the old and the new eras. Access has expanded, but with it all comes competition and expectations to specialize in your sport early, which he views as an overall negative trend.

Mr. Truschke, who played baseball at Pepperdine (1987-1990), acknowledges that while core athletic qualities like skill, determination, and resilience remain unchanged, the context around college sports has altered significantly. The introduction of athlete compensation now depends on athletes who want to monetize their college experience, a concept that was never brought up in past generations.

Structural changes are reshaping college opportunities. The emergence of NIL deals and the transfer portal has created a more fluid athlete market, similar to free agency in the professional leagues. This gives players more control but also goes away from the traditional recruiting norms. The transfer portal has dramatically increased layer movement and affected how coaches are now building their rosters. This impacts how competitive college athletics have become as both a sport and an industry.

Despite these shifts, one truth stands out. Whether in Schultz’s persevering preparation, Castro’s focus on specialized skill, or the old school emphasis from Willens and Truschke, athletes must still commit deeply to their sport. But in the modern collegiate era, success is not just based on discipline, but on strategic exposure and the ability to navigate a landscape that bridges the tracks between athletics, technology, and business.