Journey to the South: A Walk through History

Joanne Bland had witnessed the rhythm of history, watched justice rise and fall with its cadence.

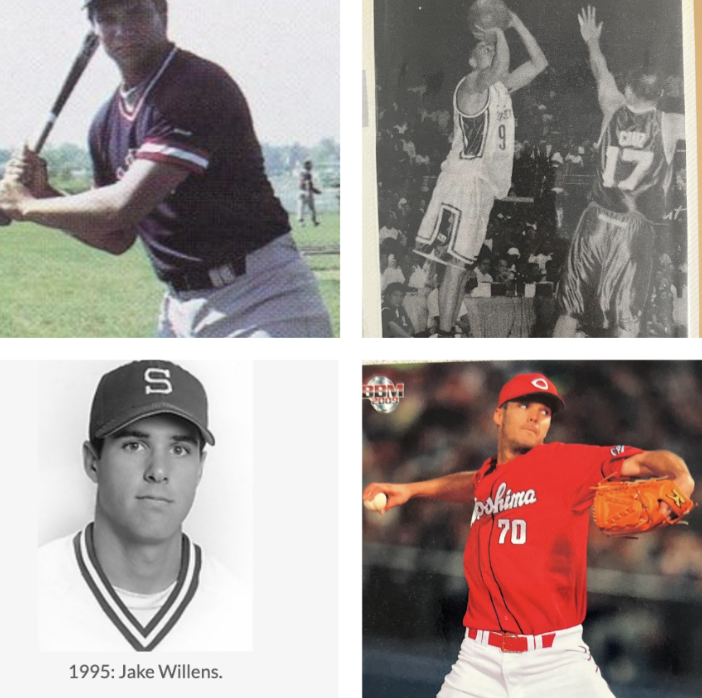

In Birmingham’s Freedom Park, statues commemorate four young girls killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing.

The journey began in Atlanta, Georgia. I remember how all the trees made it look like Oregon from the times we’d visited my grandparents there. Great pines whizzed by and blurred together through the bus window, concealing indefinite lengths of forestry behind. I was cold and unsure whether to be excited or to dread the impending tour through the American South. It seemed trivial to contemplate, so I slept.

The following day was filled with museums, the history of the AIDS quilt, travelling, and more museums, each shedding a unique spotlight on a different angle of history. A trail of museums, like bread crumbs, led us to Montgomery, Alabama, where we spent the night. Morning brought Selma, where we interacted with history for the first time.

She stood before us like a lioness, fierce, attentive, aware. Her eyes had witnessed the rhythm of history, watched justice rise and fall with its cadence. She knew why she was there. Not there on the sidewalk in front of the concrete steps we stood upon awaiting her address, but there in the world, walking with the same legs that walked through a revolution, seeing with the same eyes that saw Martin Luther King, Jr. lead a people into the future, and she was sure of her every move. When she spoke, she knew what she said was important, and somehow we did too, if only by nature of being in her presence.

Joanne Bland looked as though she might drop a seed here or there, and the next day there would be a forest where previously there was nothing. She must have been old, but her spirit and energy hadn’t aged with her. Unlike most elderly people, Bland was not jaded, rather, she possessed a hope, a spunk that was characteristic of the young and naive, and it was infectious. She’d witnessed the worst manifestations of racism and baseless hatred in her lifetime, and yet here she was, so sure, so hopeful, but not at all sheltered or unaware.

Bland had marched for her rights, her freedom, at the age of 11. She and hundreds of other brave, upstanding African Americans risked everything to resist the hate that ruled their lives and our country, all for the same hope. We stood, captivated by her every word, as Bland fearlessly shared a story of strength and perseverance in the face of circumstances we’d only ever read about in history books. In the march now known as Bloody Sunday, 11-year-old Joanne Bland and her sister were both badly beaten, along with the hundreds of other brave, upstanding African Americans who’d participated in peaceful protest for change.

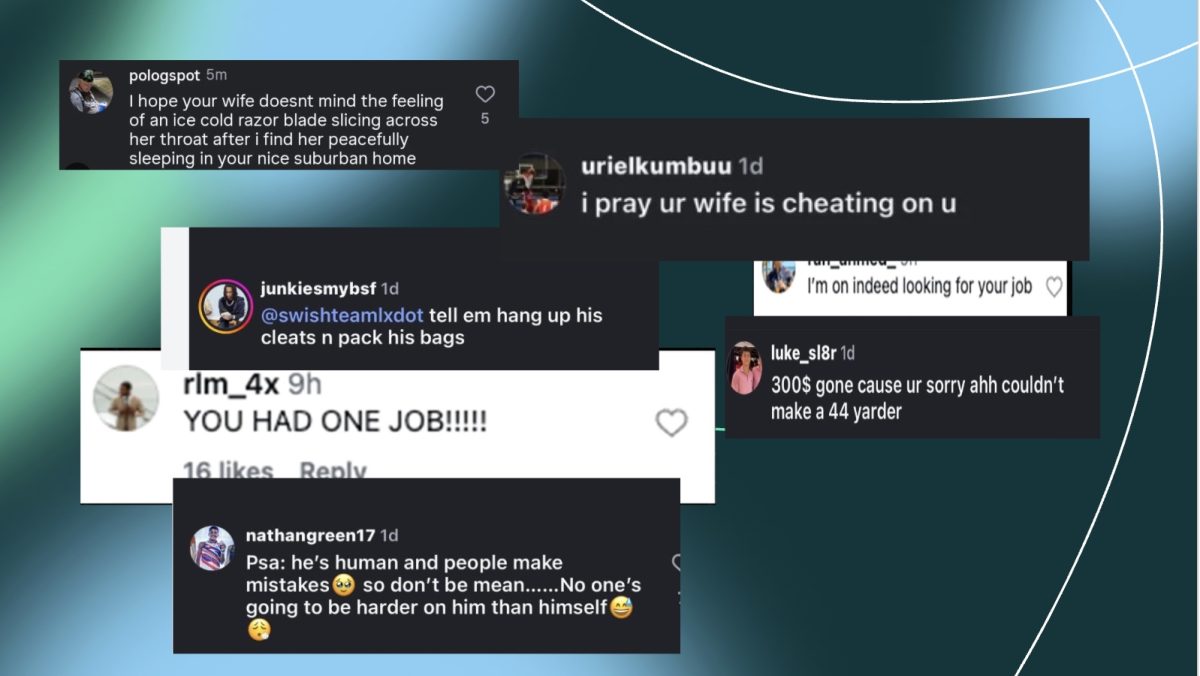

She warned us against losing our humanity over toxic emotions or common prejudices. Stay informed, she instructed, but more importantly stay active. Trying to understand where someone else is coming from can be the most powerful skill of all. While she’d seen change and her experience was one of a different time, she warned us not to write its message off as history. It was a learning opportunity, a guideline for the present and future, not an isolated tragedy, horrible but arbitrary in its occurrence. Her message wasn’t even about her personal story, but rather about recognizing patterns from history in the modern world, and addressing them before they get a chance to manifest themselves.

It was a hard message to ignore, especially as we walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where the Bloody Sunday march had taken place.

We went next to Birmingham, where history would speak to us in the form of Bishop Woods, who seemed to be a walking encyclopedia with an infinite breadth of knowledge regarding the Civil Rights Movement. I remember waiting with my classmates on the cold pavement of a courtyard in Birmingham, intensely studying each passerby, trying to predict which one might be the famed Bishop. Naturally, he came from the other side of the courtyard, where I and my small group of theorizing peers had little visibility, but he hobbled his way up to the front of the whole group, smiling and shaking the teachers’ hands. He was a small thing, short and stiff with a hunched back, but when he opened his slightly misaligned mouth, all of his oddities and frailness seemed to disappear.

Bishop Woods spoke passionately and in varying degrees of volume. When he raised his voice, heads snapped up and spines straightened with attentiveness. It was a wonder such a strong sound could come from such a small man. The bishop’s energy, though, was what kept his audience’s interest. It radiated from him like heat from an outdoor lamp, and we huddled around it like moths in the cold Alabama evening.

Gesturing flamboyantly and letting out periodic, abrupt shrieks that conveyed his passion and investment in the message of his address, he might as well have been preaching his first sermon. For a man who must have delivered this very speech more times than he could possibly remember, his charisma was remarkable, as though he was speaking of concepts new and fascinating to him, exploring new veins and crevices in a story as old and familiar to him as the back of his own hand. With vivid detail, the bishop recounted to us his experience marching alongside Martin Luther King, Jr. in his youth for his rights and freedom. He led us in song and enthusiastic dance inspired by the environment of protest and social change that embodied the Civil Rights movement. Freedom from slavery is not freedom from social oppression, the lyrics alluded, and therefore would not be tolerated as a sufficient victory. Through this joyous engagement in song, the bishop managed to interact with us in a way that elevated the collective energy of the group and broke down the formidable barriers of exhaustion, hunger, and unfamiliarly-low temperatures setting us further apart from the present moment, and reached out his weathered hand to lead us, just for a few moments, into history.

He didn’t stand in front of us to state facts we could research online. Bishop Woods was the search engine, and he allowed us to glimpse the past on a personal level- no dates, no generalized statements, no analytical perspective on the likely nature of social interactions between members of structured societal classes during the time period- he showed us history from the point of view of a real human being with real emotions and responsibilities. With the bishop, history was a mirror, and he angled that mirror in such a way that we, a group of high school millennials from California, could see our own reflections in it.

Our final stop was Memphis, Tennessee, where we would spend the next one and a half days before departure from the south. Beale Street was, of course, a must-see item on the list. We stopped there for lunch and free time. Two of my friends and I picked out quite the southern-looking diner on the very first street corner and found a table. We sat and chatted with the people at a table near us until the waiter came to take our order. I wasn’t too hungry, and thus felt less than adventurous in terms of branching out to try “southern food,” so I ordered chicken tenders and fries. When the food came, I felt even less hungry, and could stomach no more than half a bite out of one of the tenders. After offering the rest to virtually everyone within earshot, I resigned to asking for a to-go box, knowing I wouldn’t eat them later, but unable to bring myself to waste a whole meal. My friends finished their lunches, and we set out to explore. There was a trinkety little shop across the street from the diner, so we headed there first.

It was on the front steps of that shop that I noticed something- no, someone- huddled in the crevice between the cement stairs and the pavement. A man, elderly and frail, sat quietly shaking a cup of a few loose coins while passers by completely ignored him. He smiled up at me, revealing crooked, broken teeth behind his unkempt grey beard. His dark skin nearly camouflaged him behind the many layers of dark jackets he wore to ward off the cold. I smiled back at him, hating the irony of the situation that placed me standing on the stairs above him, smiling sheepishly down at his measly plastic cup of coins.

I followed my friends inside the store, choking back the vomitous feeling circulating in my stomach, telling myself it was the diet I’d had during the trip. Watching my friends pick out souvenir t-shirts and key chains only made me feel worse. They hadn’t seen him, they weren’t deliberately ignoring someone in need, but I certainly was. The sound of a few, small coins scraping the bottom of a stained plastic cup shaken by a frail, old hand crescendoed in my brain until I caught myself staring at the open door to the shop, knowing what lay just outside it. I looked down at the to-go box of chicken tenders and fries in my hand that I would never eat. Suddenly I knew how to stop the churning in my stomach.

With a deep breath, I began making strides toward the entrance to the shop, descending the stairs to level myself with the man. He was already smiling at me, a traditionally friendly gesture that somehow managed to break my heart just a little. “Hi!” I said, not expecting a response. “Hello! What’s your name?” he replied, far more cheerful than I’d seen anyone in months. I was taken aback, but his smile was infectious, and I found myself grinning widely as I talked to him. He asked not for change, but what we were all doing there, what the point of the school trip was, where we were from, and whether I’d enjoyed myself in the south. It was an educational Civil Rights journey, I’d informed him, and we were travelling with a school from California, where most students had never been to the south in their lives, including me. For someone without a home, food, money, good health, or even full use of both legs as I’d find when he eventually stood, he seemed far more interested in whether I was having a fun time in Tennessee than his own well being.

His brown eyes lit up when I spoke about our Civil Rights journey, answering all his questions about the museums we’d visited and people we’d met as though it were the single most fascinating story he’d heard in his life. I, on the other hand, struggled to understand him when he spoke. Years without dental work were evident in his speech, as was a heavy southern accent and dialect to which I wasn’t yet accustomed. After multiple attempts at understanding his name when he told me, I gave up for fear of offending him and pretended that I finally heard it. That felt worst of all, when I couldn’t even get his name.

“Well I was, um, actually wondering if maybe you’d, um, want this? It’s a bunch of chicken tenders and fries I just ordered from that restaurant over there and then I didn’t eat any of it because I wasn’t hungry, but it’s all fresh and good, I just didn’t want it and I thought maybe you did? I was just wondering.”

Once the words started coming out, I felt myself running them all together and speaking in a circular and apologetic manner that was so unlike me. It dawned on me as I was offering him the lunch I didn’t want that he could take offense at my offer, which was the farthest thing from what I wished to accomplish. The result was a rapid-fire of words spoken while continuously shifting my weight from one foot to the other as I attempted to work through my own unease. Relief flooded through me when the man graciously accepted the meal, smiling even wider than before. He thanked me profusely, and I assured him it was no sacrifice to me.

Sarah Golden • May 22, 2019 at 10:06 am

Gorgeous piece- your descriptions of J. Bland and Rev. Bishops are so vivid that even if I hadn’t met them, I would see them. And the final anecdote is told in a way that demonstrates your compassion. Well done.