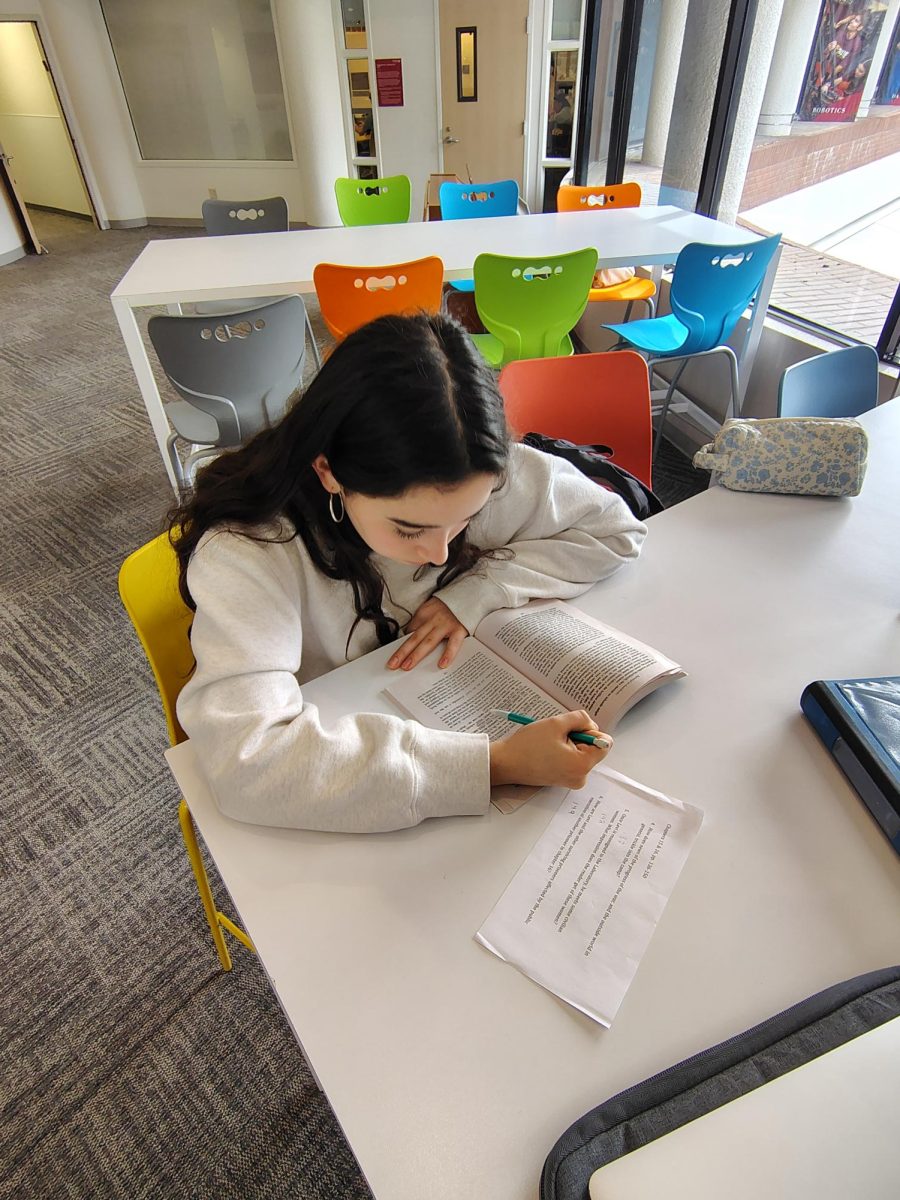

The Lunch Counter Experience

March 14, 2017

This is a creative rendering of the interactive “Lunch Counter Experience” exhibit at the Center for Civil and Human Rights Museum in Atlanta, Georgia (which the 11th grade visited on February 27).

Ding. The door creaks open. Dozens of eyes glare our way, immediately designating us as outsiders.

A bead of sweat runs into the crease of my eyelid, hindering my already poor eyesight.

I inhale deeply and proceed to follow my brethren into the restaurant.

I can feel the intensity of eyes judging my every move. It’s incredible how the act of seeing, an act so simple, one that enables people to visualize the beauties of the world, can make a person feel so scared and alone.

One by one, each man before me sits in front of the counter. I slowly approach the sole available red stool. It’s different than the rest. Maybe it’s the lighting, or the way the shadow is cast against its leather-covered surface.

Despite my better instincts, I sit down on the cold, unwelcoming red stool.

I sit up straight, until my spine reaches its greatest length. I gleam with pride as I remember my 5th grade teacher, Mrs. Caroline, telling me to pretend I had a string pulling my head up towards the sky. I smile at the youthful innocence this thought catalyzes.

I look calmly ahead, careful not to make eye contact. “Can I please have a cup of coffee?”

Scattered footsteps fill the small coffee shop, and I know exactly where they’re heading.

In an instant, the shuffling comes to a stop. Fear prevents me from turning around to face the mob of people presumably behind me.

“What are you doing here, nigger?”

I can feel the steady beat of my heart pounding. The room-filled hatred is palpable. I want to run away and never come back. But I don’t. My body sits still.

I remain silent; however, my head swirls with thoughts.

“Nigger, you have no place here.”

I can feel the faint breeze of his voice on my warm neck. I know he’s not too far.

My tongue circulates the outskirts of my mouth, carefully caressing my cracked lips before receding back into its dry, desert-like cave.

“Did you hear me, nigger? Get up.”

I hear the sound of his voice, but his words have no meaning. I close my eyes. I am not moving.

“Get up.”

The humming of his voice sends chills down my spine. The hairs on my neck are uncomfortably aroused by the warmth of his breath.

My hands clam up, sweating profusely against the now damp granite top. The rapidity of my heartbeat leaves my chest in pain. I’m scared out of my mind, but they can’t know that. I hear they smell fear.

“Get up.”

This is my last chance to walk through that door unscathed. But what good would that do? Cowards do not create revolution. If I leave now, I am surrendering to evil. I am blatantly allowing discrimination to continue before my own two eyes.

If I scamper out that door, I may leave physically untouched, but the psychological damage would be complete. I’m not doing this for me – I’m doing this for something bigger.

I’m doing this for my little baby girl, so sweet and pure, who comes home from school with bruises up and down her frail body, who wakes up with tear-stained cheeks, who will always think she is unworthy of love.

I am doing this for my son, who makes stupid, impulsive decisions, letting the white man win, who experiences a pain unfathomable to any socially accepted teenager, who will always be regarded as a delinquent, regardless of his courage.

I’m doing this for my beautiful wife, who lives in constant fear of having to protect her children from hatred, who has become accustomed to covering my daughter’s ears when racist slurs are hurled our way, who was berated by a privileged white man when her large, impregnated stomach prevented her from standing up fast enough when he demanded her bus seat.

I’m doing this for those who came before me, who were unrightfully prosecuted, who lived their short lives discriminated against, whose doors got shot open on otherwise beautiful autumn days.

I’m doing this for future generations, who will otherwise be born into cruelty, whose innocence needs not to be corrupted but preserved, who need to be educated about the past in order to prevent reoccurrence in the future.

I sit firmly in my seat. I refuse to leave.

My mind goes blank as my head is jarred left. A sharp pain engulfs the right side of my face as it hits the cold tile floor.

My face feels hot. A liquid drips down the side of my sensitive cheek, drop by drop. It tastes so salty.

“I don’t think you understood me, nigger. No one wants to look at a dirty nigger during lunch. Leave.”

I realize I am about to endure the white man’s wrath for the entire black community on my one body.

My brown haired head is jerked upward, only to be slammed back down against the hard marble floor beneath me.

Before I have time to regain full consciousness, a black shoe is lodged into the flab of skin in my stomach.

I’m doing this for my daughter.

An immaculate white plate smashes over the top of my already bloody head of hair.

I’m doing this for son.

A knife runs alongside my arm, exposing the light, vulnerable skin hidden beneath a chocolate layer.

I’m doing this for my wife.

A knuckle collides into my dark brown eyes, eyes that still have hope to see a better future.

I’m doing this for those who came before me.

An intense pain blooms in my right ear. A ringing sensation progressively grows louder, drowning out the racial slurs and yelling.

I’m doing this for future generations.

I slowly open my eyes, locking gazes with the white man standing above me. In his gaze I see contempt, disgust, and something else. Something like uncertainty. And within me I feel a small glimmer of hope.

Then the world went black.