Growth Above Grades

May 25, 2017

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of The Prowler.

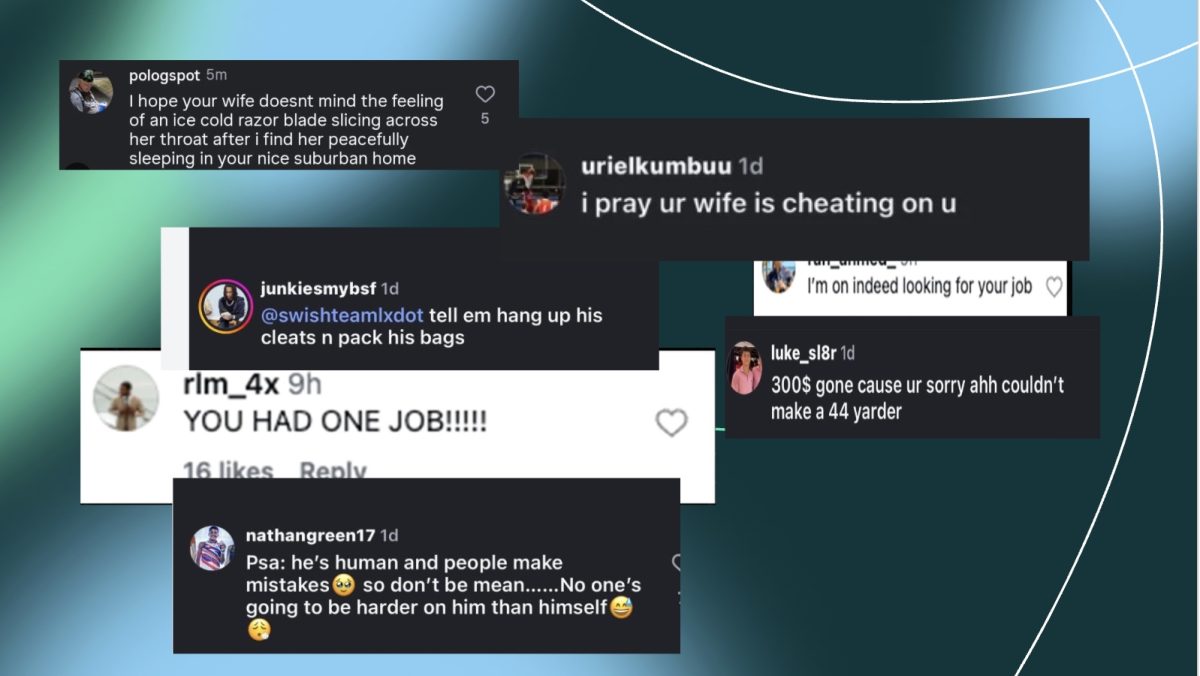

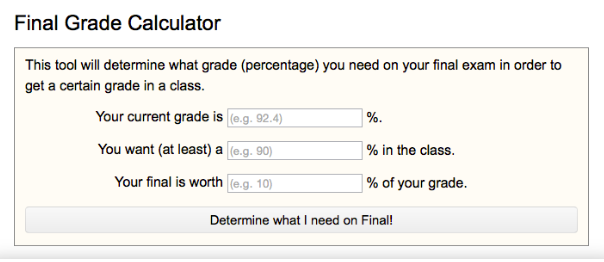

Consider the number of times that you have had to beg a teacher for a few extra points on a test. Think about the time that you had convinced yourself that your 89.4 was the difference between a college acceptance or rejection, or the number of times that you entered your grade into RogerHub in the weeks leading up to final exams.

When did this become the focus of education?

In an ideal world, a student is judged not on ability alone, but on the progress it takes to reach a certain point. And yet, the traditional system of grading does not leave room to express progress, nor does it leave room for interpretation: an A is equivalent to excellent, a B to good, a C to not so good, a D equates to bad, and an F (or an NP in de Toledo’s vocabulary) is equivalent to failure.

The symbol leaves the impression that if you are capable of getting an A, you don’t have to worry about growth because there is no higher achievement. Without arbitrary letters and symbols that dictate a person’s intelligence, students become aware that there is always room to improve, that a good grade is not the purpose of education.

Mrs. Golden, dTHS English teacher, attended an alternative school within her public high school, which consisted of classes in a more personalized education program with no grades.

Rather than grades, everything was portfolio based, so any work completed by a student was collected in a portfolio, and students were given constant feedback on their work throughout the course of the year.

Through this model, students would revise and improve any work, and by the end of the term, present the portfolio for a final assessment. Rather than receive grades for each assignment or semester, students would receive a one page narrative from each teacher, which described areas of excellence and areas where they needed to improve.

“I loved this model because it took the emphasis away from the product and put the emphasis onto the process,” said Mrs. Golden. “Can you show what you have learned and what you know? Are you showing mastery of content and skills? This model allowed for me to understand and appreciate education in a new way.”

“My experience completely changed the way I see the world,” she continued. “I don’t see the world as ticking off boxes, or the product that I am going for. It changed me as a student because I realized that teaching is an art. If a student believes in what we are doing, then there is the motivation to do well. When there is no risk, and no grade associated then maybe you take more risks, maybe you can be more original and more interesting.”

Although once intended to be utilized as measurement of improvement or growth, the traditional system of grading has since become a carrot or a stick for teachers to force students to do the assigned work.

In a statement published in The Paper Graders, a blog that discusses education led by a group of practitioners, Sarah M. Zerwin, a high school English teacher, said, “We threaten grade penalties for late work. Or we say things like, ‘This assignment is worth a lot of points so you better take it seriously!’ We give them graded reading quizzes to get them to read.”

“We put grades on pieces of writing and invite them to revise – not because revision makes them better writers but to “bring up their grade” on the paper. Parents sit down at conferences and the first thing we do is pull up a student’s grades and talk about what’s going well or not going so well.”

With a system that promotes threats and penalties, students are not taught to value intrinsic motivation, or the desire to find interest in what they are learning.

When a student finds passion, interest, and overall enjoyment in what they are learning, the grade becomes meaningless and the carrot/stick becomes irrelevant. But what have they learned? Students learn how to structure a paper, how to critically read a text, and ultimately how to get better. If a student believes in what they are doing, sees a reason to work hard, and sees how interesting learning can be, then there is a motivation to do well.

Mr. Soltis, dTHS English teacher and a strong advocate for gradeless classes, hopes to institute a nontraditional grading system in the coming years.

“By the end I expect my students to write like good college students. That is my goal, the benchmark. This means that their grammar and spelling in a recursive paper is nearly flawless, that their use of diction and syntax is eloquent, that they have style to their word choices and in how they frame their sentences, that they can substantiate their claims, knowing they must have evidence. They should be able to write from a genuine place that makes the reader interested in what they have to say, and write with a strong voice that comes from a place of interest.”

In order to ensure that this system is successful, Mr. Soltis said that it is vital that the students are aware of the expectations of the class and are able to articulate that he or she met or did not meet those expectations.

“If they have met the aforementioned expectations, then I would say they have met the expectations of the class. If they can do better, than the overall grade will be higher, and should they not meet these expectation, than the grade must be lower,” said Soltis.

“The most important part,” he continued, “is that there is a mutual agreement between the teacher and student regarding a student’s progression in the class. We would continuously check in with one another because the student should be involved in the grade. One should never be surprised by a grade they receive because they should understand how they are doing in the class.”

If the question asked is “are you growing?” and “are you learning?” then grades would reflect what each student should strive for, which is growth and learning.

There has to be an understanding that the grade reflects personal advancement, as well as meeting the benchmarks. Part of the expectation is investment, that one wants to get better. If a person starts off lower, but they work really hard, and they really do grow, than that does deserve a higher grade than may have been previously present on a report card.

The primary concern in the shift away from the traditional grading system is how one’s progress will be conveyed to colleges. Many fear that because colleges rely on grades to determine a student’s worth, a system without grades will diminish the student’s college options.

Ms. Britt, dTHS college counselor, spoke about this: “Colleges will question the meanings of personal narratives, how to interpret the transcript, and how to identify the rigor of the courses. This puts the pressure onto the high schools to fully communicate the school’s identity. It is a system that may take time to develop, but this is what we do when the college counselors meet with admissions counselors each fall.”

“This change is absolutely a possibility, and if it were to happen, colleges would have to change their own policies, which many are currently in the process of doing,” said Britt.

One of the most difficult aspects in instituting this new system is the difficulty in changing the paradigm. A paradigm, a model or pattern of thinking, communicates the set of assumptions with how people perceive the world. It is difficult to challenge a system that so many people rely on. However, change becomes necessary when people become aware that the system has many faults that must be improved, although many are reluctant to changing such a long-held, valued system.

This reluctance to change is not just the students and it is not just the teachers. It is the parents, the administration, the colleges, all who are involved in maintaining this structure. This development requires teachers who are willing to put in the time and the effort, who are able to decide what works and what needs to be adjusted.

By instituting a nontraditional grading system, schools allow for more individual and creative freedom by removing the carrot/stick and allowing students to be more original and creative. While this system may be seen as selective for the intrinsically motivated student, perhaps the opportunity to take a risk without fear of their grade being penalized, and the opportunity to communicate their passions will allow the student to become motivated.

An article written in The Columbian, a newspaper in Washington state, includes an interview with a freshman Language Arts teacher at Woodland High School (located in Woodland, California) who decided to stop giving out letter grades to his students. The teacher said, “Creativity and ideas are our main commodity right now. We need to teach students to be motivated and self-driven… School can be about learning or achievement. Grades are achievement. Learning is unquantifiable. You can’t put learning into numbers.”

By starting small and beginning a nontraditional system of grading within the humanities department, teachers and students alike can assess the productivity of this system, and whether or not it allows for an improvement in not only the student’s education, but in the student’s mindset approaching learning.

Should de Toledo decide to adopt a similar policy, many may question how this will change de Toledo’s identity. Given the fact that this system has been proven successful in highly academic and competitive environments, would de Toledo be able to develop a system without changing the identity of our school?

I believe that we can make this transition while maintaining the balance between education and community that makes de Toledo different from other high schools. However, this issue is not one that pertains to an individual school. This is a societal issue that must be resolved in order to change students’ mentality in regards to education as a whole.

Society is obsessed with evidence, data, and quantifiable numbers. Achievement is believed to be indicated by test scores from mandatory tests, which supposedly communicate a student’s intelligence.

However, students and teachers attest that this is not true, and therefore there is a problem with how we “measure” students. The question is not what the problem is, but how to solve it.

dina appleby • May 26, 2017 at 9:21 am

love this article.

Sarah Golden • May 26, 2017 at 8:39 am

A very compelling piece! Thanks so much for bringing this important idea to the table. I sincerely hope that your piece initiates meaningful conversations about teaching and learning.