Restore Circular Migration on the US Border with Mexico

“Historically, according to Massey, young men came to America to work, worked, went home, returned, and then went home once again.”

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of The Prowler.

Building a wall and increasing the cost of border control shuts down circular migration, and, instead of keeping migrants out, it keeps them in and roots them here.

In order to restore the circulation of migration, we should make the border easier to cross, reduce the size of border control, and make it easier for migrants to obtain legal status.

Douglas Massey, founder of the Mexican Migration Project, has studied Mexican migration patterns throughout the years. Historically, according to Massey, young men came to America to work, worked, went home, returned, and then went home once again.

Massey observed that between 1965 and 1985, a lot of Mexican migrants came to the United States illegally, but almost all who entered eventually returned home.

Research supports that migrants usually came to the United States for the financial incentive. However, as Border Patrol expanded, it became more risky and dangerous to return home so often–or at all.

Instead of the normal pattern of coming to the United States to work and eventually leaving, migrants were staying.

Attempts to solve the problem of illegal Mexican migration were, in reality, what caused the problem of illegal Mexican migration.

The idea of border control on the Mexican-American border was unprecedented until initiated by Leonard Chapman. A general in the Marine Corps, Chapman served in Vietnam. His job was to secure the border there.

Chapman failed at securing the border in Vietnam; however, when he retired in 1971, he took that as his chance for redemption by becoming the commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalization Services, responsible for securing the border of the United States.

The effects of Chapman’s actions are still apparent today in the rising costs of securing the US-Mexico border.

Before Chapman, Americans didn’t think that they had an immigration problem. He convinced them they did. By 1986, the Immigration Reform and Control Act was put into place, which militarized the border and increased the budget of Border Control by ten times the previous amount.

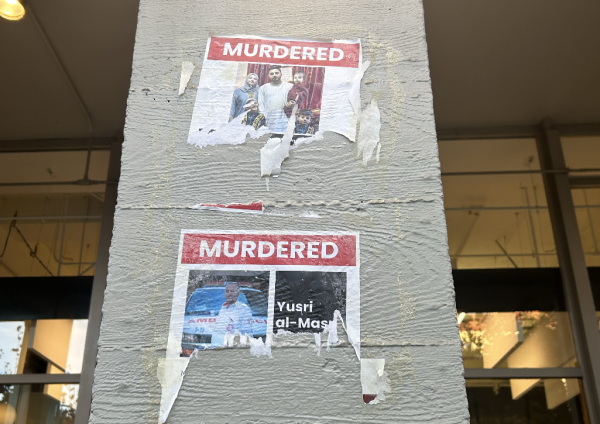

Instead of helping migrants who are seeking refuge or a better life, and fulfilling our domestic and international legal obligations, the U.S government is regularly subjecting migrants to criminal prosecution and incarceration.

“Illegal Entry”/8 U.S.C. 1325 makes it a crime to unlawfully enter the United States. It applies to migrants who do not enter with proper inspection at a port of entry and avoid examination or inspection, or who make false statements while entering or attempting to enter the United States. A first offense is considered a misdemeanor punishable by a fine, up to six months in prison, or both.

This system of punishment was created to reflect zero tolerance and to be a lesson to others so they won’t cross the border. With this policy, first timers for illegal entry are charged, including those with no criminal record or history of previous offenses.

The way this issue is dealt with, in regards to punishment, is ineffective and cruel. Migrants are being detained inhumanely and face harsh punishments as if they are just criminals and no longer human.

If migrants are traveling as a family, the prosecution could harm all members. Parents can be separated from their children, husbands from their wives. Criminal defense lawyers have observed that persecution of adult family members for entry-related offenses results in time in federal prison, away from their children. As a result, those children are placed in foster care. Parents and family members are given little to no information about their children’s’ location or condition. These families face many challenges trying to reconnect.

Criminalizing migrants is not an effective way to deter future immigration. Detaining migrants is an attempt at a deterrence policy; however, research shows that it only has a weak effect in reducing illegal immigration.

Separating families as a deterrence does not have a clear success rate either. In 2017, the separation of families was followed by an increase in the number of families crossing the border illegally. This raises the question of the validity and effectiveness of this punishment and if it should still occur.

Due to the emphasis on entry-related offenses at the border, resources and money that could be used for more serious crimes, such as drug smuggling and human trafficking, are wasted. The conviction of migrants illegally crossing the border also increases the population of already overcrowded federal prisons.

The system is also flawed when it comes to convicting migrants: a prosecutor can pressure the migrant to plead guilty, and as a result they are forced to give up certain rights such as their right to a trial and the right to challenge the conviction. This process moves quickly, and if migrants plead guilty, they can be sentenced in a matter of hours instead of after careful analysis of each case.

Migrants seeking asylum are being denied their right to protection, which includes “all activities aimed at obtaining full respect for the rights of the individual in accordance with the relevant bodies of law,” violating international law.

Advocacy groups, as well as other individuals, have reported that officials from The Department of Homeland Security have denied migrants their right to pursue asylum or protection and have instead pressured them into dropping their claims in exchange for plea agreements.

This causes a big problem with our due-process clause, which states that “no one should be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law.”

Keep in mind that most migrants coming to the United States might not speak English or fully understand the extent of the situation they face.

Migrants are deprived of individualized hearings and often meet their attorney the day of their hearing and only have minutes to discuss their case with them. They are forced to put their lives in the hands of someone who knows nothing but the basics of their case and who can’t fully defend them.

My name is Leila Wazana and I am a senior at de Toledo. This is my first year writing for The Prowler and I am excited about what I can contribute. I look...